DNS Servers, Security Issues, and Options for Business

This document explains some of the technical details of DNS. Specifically, it:

- explains how DNS works;

- reviews how your ISP assigns you to a DNS server, and which servers they most commonly use;

- provides examples of third-party DNS providers you can use to protect from DDOS attacks;

- explains the A, AAAA, and MX DNS records;

- highlights security issues with DNS open resolvers; and

- discusses how governments use DNS for censorship.

DNS Defined

DNS (domain name servers) translate domain names into IP addresses. This allows a user to look up a company by a simple name such as coke.com, instead of by a complicated number, like nnn.nnn.nnn.nnn.

A company can run their own DNS servers, but most companies use DNS servers operated by their ISP or connect to one of the public DNS servers, such as Google or OpenDNS.

How DNS Works

ICANN is the organization that oversees the assignment of IP addresses worldwide. They assign blocks of IP addresses to different countries and different registrars around the world for top level domains (TLDs). For example, the .com domain is operated by Verizon Business. In Russia, the top level domain .ru is run by The Coordination Centre for TLD RU, which is a pretty boring name.

When a person registers a new domain they get an IPv4 and, optionally, an IPv6 IP address for their domain. When a user types a domain into their browser, their computer sends a DNS lookup to a DNS server. The DNS server tries to resolve the IP address by looking in its cache. If the address is not found it will query other DNS servers. This request could go all the way to the TLD DNS servers. Usually it does not have to go that far as a DNS server nearby will have the IP address in its cache.

DNS records have an expiration of a few hours. So if you change an IP address, it usually takes a few hours for those cached records to expire and for the new IP address to take effect.

DNS Settings on your Computer or Smartphone

When you use your cell phone, or connect to the internet in your office, the DNS settings on your computer are changed to a DNS server selected by your internet service provider (ISP) or wireless carrier. The DNS settings might be set to the internet router in your office, which basically does the same thing since it sends out the DNS lookups to the DNS server assigned by the ISP.

You can override the DNS settings on your PC or cell phone if you want to pick specific DNS servers. Many ISPs and wireless carriers use Google or OpenDNS instead of their own DNS server since Google and OpenDNS have cached replicas around the world. Presumably they could return a DNS query a few milliseconds faster than other servers. That would reduce latency for people in different parts of the world who are looking for your website.

DYN.com and Cloudflare

Companies that have more than one data centre usually use a third party high-availability DNS provider like DYN.com. They failover their customers to a redundant site in the case of an outage by changing the DNS records. They also provide assistance during DDOS (distributed denial of service) attacks. A change at DNS.com takes effect immediately for the company, since the client is using that DNS server and not a public one. So the company does not have to wait hours to get back online.

Cloudflare is another company that helps when a website is under a DDOS attack. They do this by proxying your web traffic to their enormous data centres temporarily. Then they block DNS lookups that look like they are coming from hackers.

DNS A Record

There are different types of DNS records. One domain usually has several. The A record gives the IP address of the domain’s website.

On Linux systems you can use the dig command to query a DNS server. Or you can run it online at different websites.

For example, here is the A record for anturis.com.

In the screen below, I selected the DNS servers at Google. The website shows me that the IP address for Anturis is 67.225.148.163. This means that I could enter https://67.225.148.163 to open the Anturis website instead of the domain https://anturis.com (Anturis forwards all their http traffic to https, so if you enter http:://67.224.148.163 nothing will answer) in order to skip the DNS lookup.

DNS MX Record

The MX record for a domain is the FQDN of the domain’s email server. When an email server sends email, it queries the DNS MX record for the domain of the email recipient. It then sends mail to the MX record with the lowest priority. It uses the next server priority if the first one is busy or not available. Email is send using SMTP which is an interactive conversation. Thus there is a limited number of SMTP connections available per mail server. For this reason it’s often the case that the first server is busy.

The MX record is a domain name and not an IP address. Most of the time domain names in the MX record have a dot (“.”) at the end. It does not mean anything. It is just a convention. The mail server would have to remove the dot to resolve to a valid IP address.

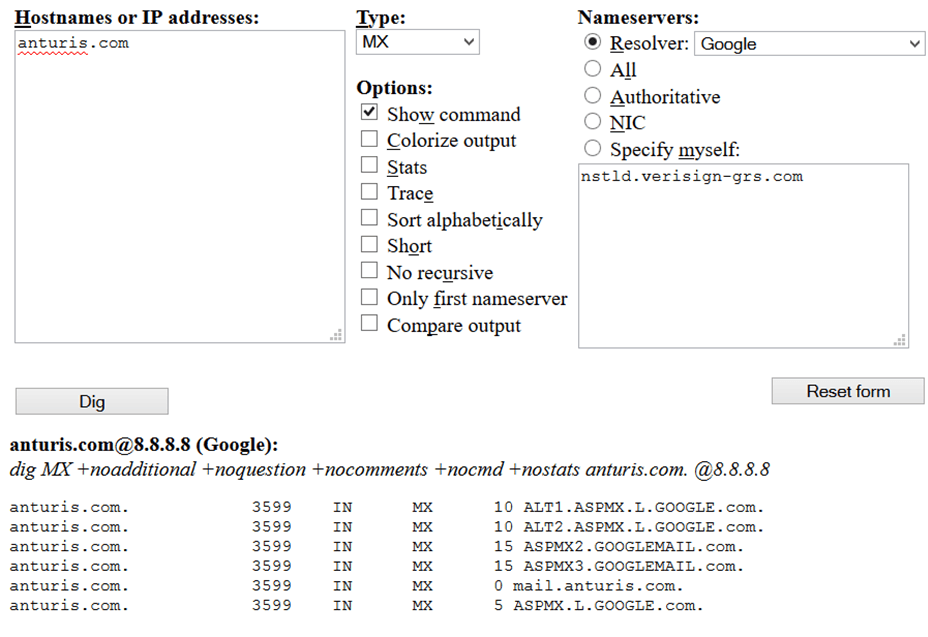

In the example below, you can see that Anturis uses Google for email.

OpenDNS and Encrypted DNS

DNS has two security issues: open resolvers and the fact that DNS lookups are not encrypted.

When you are using a VPN connection such as IPsec to connect one data centre to another, or to connect to your company’s network with your laptop, DNS lookups are in clear text. They go around the VPN tunnel. This means a hacker knows what addresses you are looking up if they are snooping on your traffic.

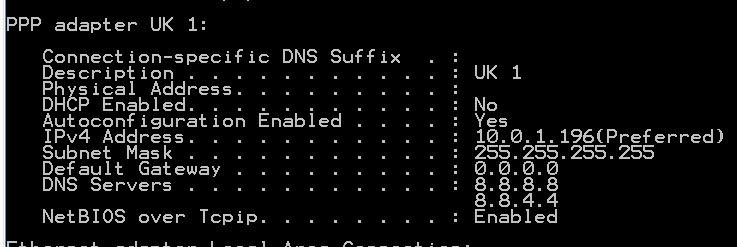

Here is how to illustrate that. I have connected to a VPN, so my traffic is going out over IP address 10.0.1.196 per the routing table. As you can see the VPN company I have connected to has set my DNS IP address to use Google for DNS lookups (8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4).

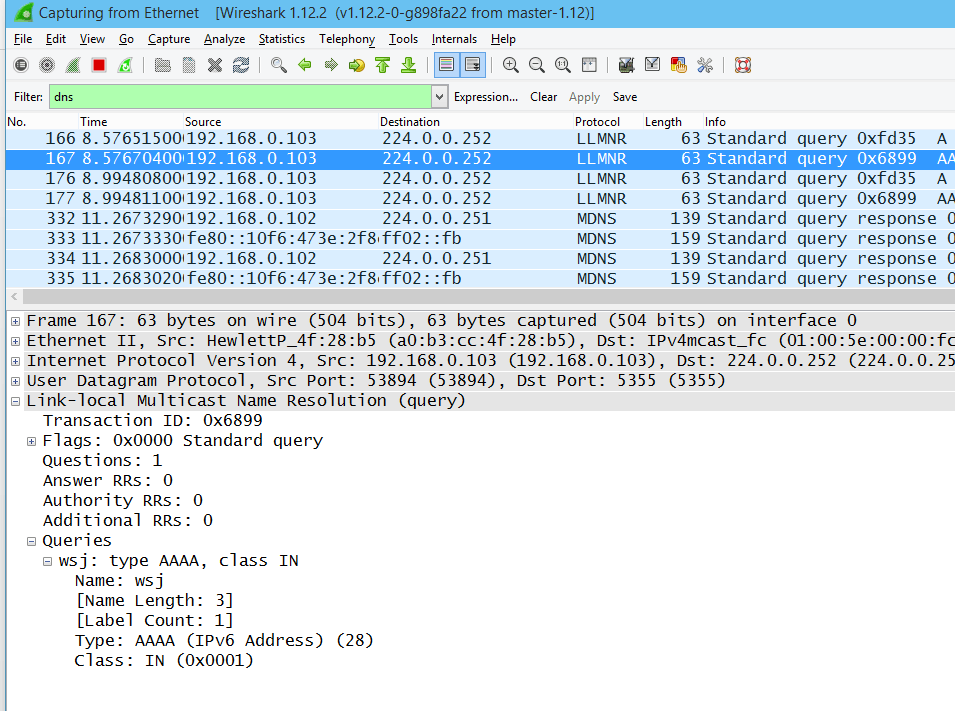

Now, if I type “wsj” in the browser looking for The Wall Street Journal, my computer sends out a DNS lookup, asking for the IPv6 IP address (AAAA record) for “wsj”.

I used Wireshark to snoop the traffic going out my laptop. You can see that the DNS lookup is going out in clear text. If this traffic was encrypted you would not be able to read the text in the packet.

If you want to make your computer send out DNS lookups using encryption, you can install DNSCrypt from OpenDNS by downloading it here. You can only use that with their DNS servers, since encryption is not part of the DNS standard.

The Open Resolver Problem

A DDOS attack is designed to take down a website. Often this is done by having DNS servers greatly amplify the DNS lookup and then forward that data to a webserver. This is possible because the IP address for the recipient can be spoofed. In other words, it can be set to whatever value the hacker wants. The DNS server does not check it. This is because of an older DNS design, which lots of DNS servers still have not fixed.

You can read more about this at the Open Resolver Project.

Government Censorship

Some countries, including Turkey and China, have poisoned DNS servers to block websites. They do this by adding fake DNS records to DNS servers. Those addresses have the wrong IP address, thus blocking sites like The New York Times in China. In China, all internet traffic is required to use government-approved DNS servers.

Turkey’s censorship is not so sophisticated. There, when the government tried to block certain websites last year, people went around painting the IP address of Google’s DNS servers on the walls of buildings: 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4.

So this is a basic summary of some of the technical details, options, and issues around DNS. The main take away message is that most people use Google, like they use Google for everything else, although you do have different options for your company. Also key is the message that you should partner with another company to provide DDOS protection for your site.

Leave a Comment